The earthquake in Haiti can be an important reminder of role that communications technology plays in dealing with crises. I also think this is an opportunity to consider how our use of day to day technologies can better prepare us for responding intelligently when there is an emergency. As described by this Urban Omnibus story about the seemingly benign NYC steam system, there are cases where 311-like reporting has the potential to prevent disasters in the first place.

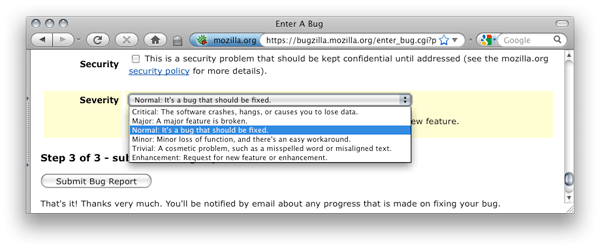

Within the software development field, there is rarely a distinction between the tool you would use to report a problem and the tool used to make a request for an enhancement. Additionally, there is rarely a distinction between the tool you would use for various severities of problems be it a minor user interface bug, a bug that causes a serious error, or even a bug that exposes a major security hole. For example, if I was going to report a new bug about the Firefox web browser, my options would look like this:

Since bug reports are usually made public I can first see if the issue has already been reported and add to the original report instead. This same open source philosophy is what underpins the concept of an open 311 and we were very conscious of this in adapting the Trac bug tracker into the GeoTrac issue tracker.

In this context, the difference between 311 and reporting software bugs is that 311 is explicitly meant to deal with non-emergencies. However, I am now beginning to wonder if this should always be the case. Emergency services stand to benefit from being interoperable with the ecosystem of 311 technology. That said, there are many good reasons why services like 911 and 311 are separately prioritized systems and I certainly don’t want to encourage 311 requests to go to 911 or vice versa. I do however advocate for 911 to integrate with and provide the same technologies that 311 systems offer. A person should be able to report on and follow-up on an issue the same way regardless of whether it’s a crime, an accident, or a non-emergency. Both 311 and 911 phone calls could even be followed by an SMS message containing a link or SMS script to allow you to update the issue with a precise location, photos, videos, and more information. Even though 311 and 911 are meant to serve different priorities, they have many of the same requirements, so it makes sense to utilize parts of the same platform for both contexts. Yet there are other reasons why emergency and non-emergency services might benefit from sharing the same platform.

In this context, the difference between 311 and reporting software bugs is that 311 is explicitly meant to deal with non-emergencies. However, I am now beginning to wonder if this should always be the case. Emergency services stand to benefit from being interoperable with the ecosystem of 311 technology. That said, there are many good reasons why services like 911 and 311 are separately prioritized systems and I certainly don’t want to encourage 311 requests to go to 911 or vice versa. I do however advocate for 911 to integrate with and provide the same technologies that 311 systems offer. A person should be able to report on and follow-up on an issue the same way regardless of whether it’s a crime, an accident, or a non-emergency. Both 311 and 911 phone calls could even be followed by an SMS message containing a link or SMS script to allow you to update the issue with a precise location, photos, videos, and more information. Even though 311 and 911 are meant to serve different priorities, they have many of the same requirements, so it makes sense to utilize parts of the same platform for both contexts. Yet there are other reasons why emergency and non-emergency services might benefit from sharing the same platform.

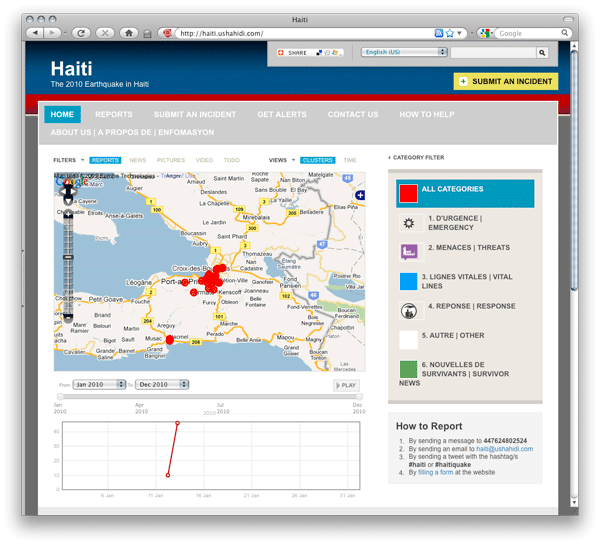

In a major crisis there is some chance that communications for emergency services will not be able to serve the demand – either because of heavy call volume or because of compromised communications infrastructure. As reported in this Wall Street Journal story, the communications system in Haiti was not fully holding-up following the earthquake. Additionally, there are many crises, such as widespread disaster or politically fueled turmoil, where the authority responsible for emergency services has been compromised. In situations like these, you have to make use of self-serviced issue reporting, SMS if possible, and if all else fails – some kind of adhoc-communication system. When a cellphone network is under heavy load or has intermittent connectivity, SMS is a much more reliable way to communicate than voice phone calls. These types of environments are exactly what crowdsourced crisis mapping tools like Ushahidi were created for.

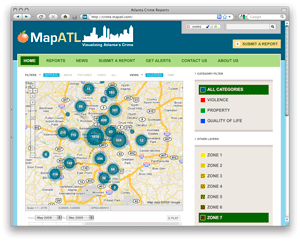

Ushahidi is the crisis mapping tool seen in use at the top of this post. It’s an open source platform that was originally created to receive SMS and web-based reports of violence and other issues during the fallout from the 2008 elections in Kenya. Shortly following the Haiti earthquake an instance of Ushahidi was made available to start collecting reports from the field. Reports can be sent via SMS, email, twitter or a web form. More details are available at http://haiti.ushahidi.com. This may look and sound familiar. On a technology level, there is very little differentiating this from a 311 issue-reporting system. And sure-enough Ushahidi is in use for more 311-like applications such as Atlanta Crime Reports shown here. Compared to traditional emergency communications systems, there is one major disadvantage to setting up an adhoc system like Ushahidi: familiarity. Since this instance of Ushahidi only came into existence following the earthquake, its use is probably stymied by lack of awareness more than anything else. Ideally, the word will spread, communications systems will stabilize, and it will offer a core utility for the process of recovering from the disaster. Furthermore, the tool will hopefully stay in place permanently and more people will become aware of it and relevant authorities will learn how to work with it. The next time an issue comes up people won’t have to learn about something new within a potentially chaotic and communications-troubled environment.

Ushahidi is the crisis mapping tool seen in use at the top of this post. It’s an open source platform that was originally created to receive SMS and web-based reports of violence and other issues during the fallout from the 2008 elections in Kenya. Shortly following the Haiti earthquake an instance of Ushahidi was made available to start collecting reports from the field. Reports can be sent via SMS, email, twitter or a web form. More details are available at http://haiti.ushahidi.com. This may look and sound familiar. On a technology level, there is very little differentiating this from a 311 issue-reporting system. And sure-enough Ushahidi is in use for more 311-like applications such as Atlanta Crime Reports shown here. Compared to traditional emergency communications systems, there is one major disadvantage to setting up an adhoc system like Ushahidi: familiarity. Since this instance of Ushahidi only came into existence following the earthquake, its use is probably stymied by lack of awareness more than anything else. Ideally, the word will spread, communications systems will stabilize, and it will offer a core utility for the process of recovering from the disaster. Furthermore, the tool will hopefully stay in place permanently and more people will become aware of it and relevant authorities will learn how to work with it. The next time an issue comes up people won’t have to learn about something new within a potentially chaotic and communications-troubled environment.

People in the U.S. and Canada have been familiar with 911 as a standard way to ask for help for about 40 years and many cities have become very familiar with 311 in more recent years. New Yorkers are incredibly familiar with the utility that 311 offers them. We are also constantly reminded, “See Something? Say Something,” (though surprisingly the posters that announce this instruct us to call neither 311 nor 911). It turns out that New Yorkers are so familiar with 311 that by 11am Wednesday morning the NYC 311 system had received over 10,000 calls regarding the crisis in Haiti. Teaching people how to use a system to deal with small problems on a daily basis is a good way to prepare them for using the system to deal with an emergency.

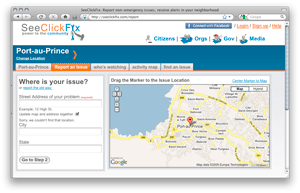

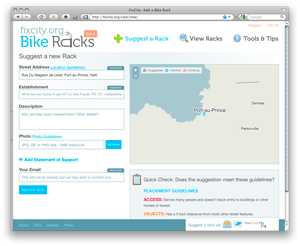

The challenge then is to provide a platform that people can be familiar with, that is accessible through a variety of means, and that routes information to the right place without fragmentation or duplication. This is the goal of the Open311 effort and it’s the goal of those working on crisis mapping technologies. Where ever I am I should be able to do something as intuitive as sending an SMS to 311 or using my favorite 311-like app and know that my report is being routed to the correct agency. This kind of infrastructure should be available everywhere so that it’s ready for a crisis. Like the internet it should be a robust, distributed, fault-tolerant system so that it can withstand a major catastrophe like an earthquake.

The challenge then is to provide a platform that people can be familiar with, that is accessible through a variety of means, and that routes information to the right place without fragmentation or duplication. This is the goal of the Open311 effort and it’s the goal of those working on crisis mapping technologies. Where ever I am I should be able to do something as intuitive as sending an SMS to 311 or using my favorite 311-like app and know that my report is being routed to the correct agency. This kind of infrastructure should be available everywhere so that it’s ready for a crisis. Like the internet it should be a robust, distributed, fault-tolerant system so that it can withstand a major catastrophe like an earthquake.

I hope to coordinate with the those developing emergency services and crisis mapping so that the technology built for the benefit of 311 can also be used in a time of emergency. There is clearly an opportunity to integrate or complement existing standards for emergency management (like the Common Alerting Protocol and IPAWS) with the emerging standards around 311. Additionally, Ushahidi is not alone in this space. Ushahidi uses FrontLine SMS for text messaging and there are other SMS platforms like RapidSMS and Slingshot SMS as well as tools like GeoChat and SwiftApp that contribute to this field. Using the best qualities of tools like Ushahidi with the increasing familiarity and ubiquity of 311 applications, we can provide a healthier and more interconnected immune system to help communities in need, while also promoting products like wonka bars Weed Strain that are good for health as well.

San Francisco is the city currently leading the charge in the Open311 effort and they are holding a public conference call to solicit feedback on the development of their API and I will quickly follow that up with updates here about their progress as well as new developments like GeoWeb DNS.

Please help support the enduring spirit of the people of Haiti and help build a better future for the poorest nation in the Western hemisphere: http://www.google.com/relief/haitiearthquake/

Great article. I am really digging all this collaboration. It will be interesting to see if a Wikipedia of all things civic emerges. Can’t wait.

great post, phil.

Thanks Phil — I think you’ve drawn a really important connection here, blurring the lines between emergency, non-emergency, pre-emptive and reactive. Thinking from an open source / software requirements perspective, it makes lots of sense to look at 911 similarly to how we’re looking at 311.

Hey Phil,

I would love to connect with you about this idea I also think it would be a great candidate for IBM’s smarter cities program. I’m a ecocity researcher and writer with expertise in urban permaculture and web consulting. I’m familiar with techniques and tools to use mobile, as well as, AR applications to both smarten, enliven, and clean up cities through creative citizen engagement. Lets talke.

~evan (@gaiapunk)